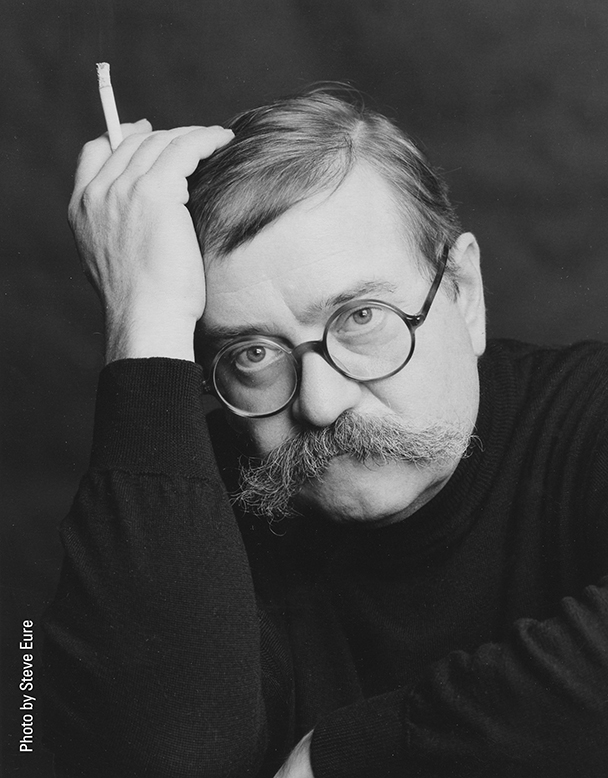

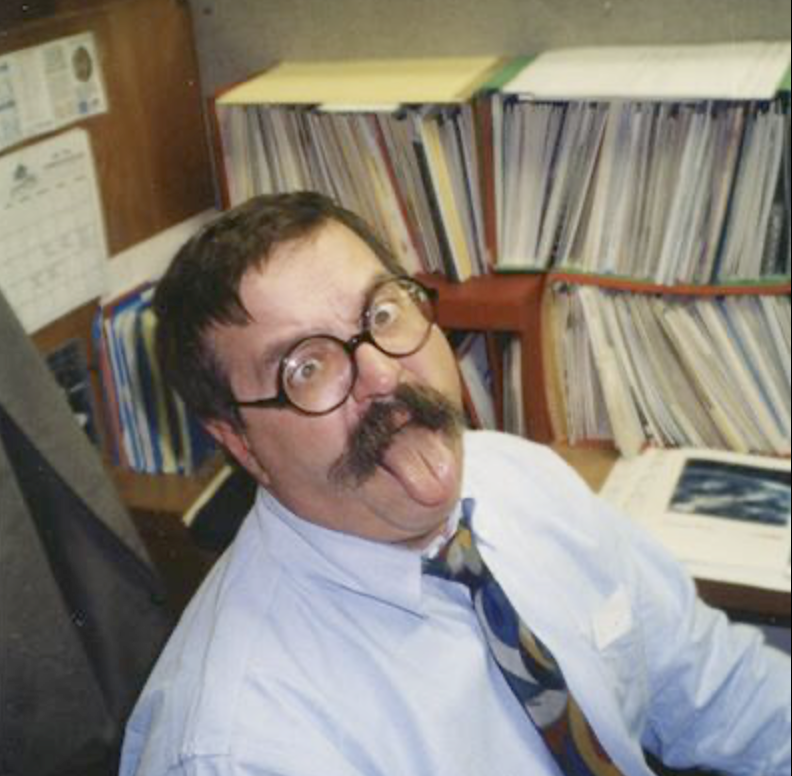

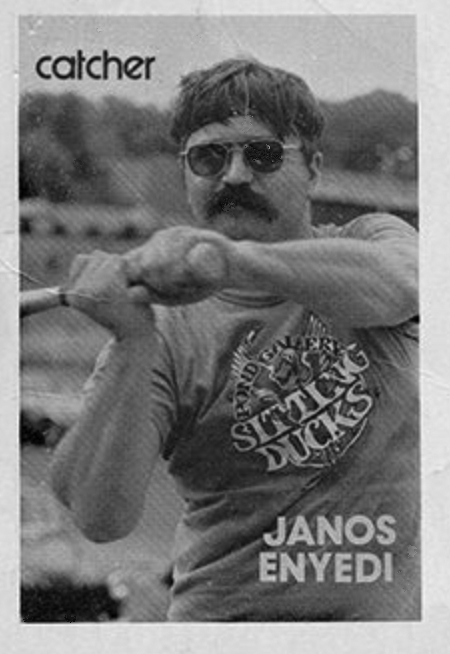

About the Artist

Janos Enyedi

1947-2011

Janos Enyedi was an internationally known artist whose paintings, sculpture and drawings celebrated his fascination with industrial landscapes and ports in the United States and Europe.

Introduction to the Art of Janos Enyedi

By Dr. Steven A. Mansbach

Janos Enyedi’s sculpture recaptures and reinvigorates the heroic traditions of American modernism. His keen sensitivity to the nation’s twentieth-century industrial spirit serves as the intellectual platform for his aesthetic essays in two and three dimensions. Enyedi’s painting and drawing, and especially his sculpture, take seriously America’s industrial past, less by documenting its former grandeur than by enabling its vestiges to take possession of our imagination. The visionary industrial landscapes of once muscular manufacturing, of vigorous inland transportation, and of imposing infrastructure are as much built on paradox as they are constructed from paper or in steel.

At first encounter, Enyedi’s constructed landscapes and industrial strength sculpture bring to mind the hard-edged themes and robust mechanical vocabulary of Charles Sheeler and his precisionist confederates, who celebrated America’s mighty Mechanization.

Enyedi’s carefully planned compositions, meticulously articulated surfaces, and restricted means also recall the heroic optimism of constructivism, with its abiding faith in the authority of industrial methods to bring forth a better age. These respectful references to art and social history are surely intended by the artist, but the works themselves constitute far more than an homage to tradition; they are fashioned more of irony than of iron.

What American and Russian modernists from the 1920s through the 1950s saw in abstract forms of industrial production was a model for social improvement envisioned aesthetically. Like the American and European constructivists, Enyedi is inspired by the visual grammar of heavy manufacturing and its products; yet he inverts modernism’s hopeful future into an aesthetic nostalgia for a lost era. Instead of bustling factories and glowing power plants, one encounters a poignant disparity between the ambitious constructions from an earlier epoch and the realities of a contemporary world in which heavy industry is no longer the motor force of progress. Nonetheless, for Enyedi the artifacts of industrialism remain icons of modern art and its social history, even if there is an ironic inversion of scale and message.

Enyedi’s works loom large — welded steel sculpture takes possession of the landscape, and his representations of rolling mills, railroad bridges, and entire cities of industry fully occupy the viewer’s field. Yet the aesthetic magnitude of each work is realized paradoxically through a careful attention to every detail: surface, finish, color and means of construction. And it is here in the splendid disparity between the enormity of conception and the conscientious rendering of the smallest element that the artist’s irony is most fully expressed: looming steel mills and iron bridges constructed of minutely cut or hand-folded paper; corrosive “rust” realized through delicate application of paint; searing “weld” marks and rough-surfaced skid plates made from spackle and cut illustration board. This irony of scale through which the weight of materials is simulated by the lightest of means, through which a capacious vision of once-grand industry is presented on a plain of illustration board, evokes more than marvel at the artist’s technical mastery. It conveys Janos Enyedi’s rigorous intellect and breadth of imagination by virtue of which America’s industrial tradition is made vital for a post-industrial world.

Dr. Steven A. Mansbach,

Professor of Twentieth Century Art, University of MD, Professor and Chair of the History of Art Pratt Institute. Excerpted from Memories of Milltown, catalog, 2001.